Becoming a Bird Trainer

By Jenna McElroy

I am the new Eagle Creek Park Ornithology Center manager and a Certified Professional Bird Trainer, but what does that mean? It means that I have been studying bird body language, raptor husbandry, and the science of behavior change for many years. I passed the International Avian Trainers Certification Board’s 200-question written exam in the fall of 2021 (iatcb.com/). In this article, I am going to tell you about how I became a bird trainer, get nerdy with the science of behavior, and express how lucky I am to work with such amazing animals and people every day.

Although I studied biology and animal behavior in college, I had little experience with animals when I started at the Ornithology Center (OC) seven years ago. I had volunteered at the Indianapolis Zoo, cleaning parrot, flamingo, and vulture enclosures, but my passion was teaching people about my love for wild birds, not captive ones. I was so thrilled to be offered the part-time naturalist position at the OC in 2015. I had no idea that it would take me down this road to becoming a Certified Bird Trainer.

At the OC, we not only serve the community as a destination for learning and exploring the world of birds, but we also train and care for multiple non-releasable birds of prey, or Raptor Ambassadors. These raptors are licensed under an Indiana DNR education permit, allowing us to keep them for on-site environmental education and off-site outreach programs. The way we view and train these raptors has drastically changed in the last five years, spearheaded by yours truly. Traditionally, nature centers have housed non-releasable animals and “used” them for public education, a worthy cause. However, in many cases these animals are treated as forever wild, meaning that their constant fear of humans is seen as natural and unchangeable. This is not great when considering animal welfare. Birds are especially hard to care for and can have very high levels of stress, even if they seem calm such as owls. Because of falconry, raptors are also traditionally kept with anklets and jesses or short leashes attached to their legs. This allows handlers to grab a hold of them and force the raptors to come out of their enclosures, even when the birds wish they could fly away.

Red-shouldered Hawk being moved inside due to cold weather and is trying to look big and scary.

A Great Horned Owl at the Indiana State Fair is hissing and not happy.

Although many of the raptors that have been kept at Eagle Creek Park in the past were trained using traditional falconry methods, the raptors that I started my career with in 2015 were NOT trained. I was taught to, very gently and lovingly, grab their leashes and hold on tight – and that is how I did programs with them. The birds were seen as wild animals and their constant fear of us was normal. They did not have names, which made sense considering our main programming message was that they were not pets, just a representation of their wild counterparts. For programs, the birds were expected to get used to being in front of giant, scary groups of people. To get them out of their enclosures, if you kept persisting, they would eventually give in. I now know that this is called “learned helplessness” and is when the animal realizes that their behavior has no effect on their environment. I learned this when I was fortunate enough, thanks to an ABAS Birdathon grant, to be sent to the Minnesota Raptor Center for a Raptor Care and Management Workshop in October 2016. I was awed by the behavior of their raptor ambassadors. They weren’t afraid of their handlers! They were trained, using food rewards, to do the behaviors that I forced our birds to do, like step onto my gloved hand, or go into a travel crate. These raptors all had similar origin stories as our raptors – injured in the wild, rescued, rehabilitated, and determined non-releasable. However, they didn’t act “wild” anymore. They were well adjusted to their new environments and seemed to enjoy their new “jobs” as ambassadors for their species.

When I got home from the Minnesota Raptor Center, I started researching and following as many bird trainers and nature centers with raptors that I could find. I learned about this new at the time movement in the wildlife education community. It is a shift away from a coercive model of “using the animal” or “grab and go” to an empowerment model based on providing the animal with choice. By applying behavioral science and a system of rewards, the animal is taught the behaviors it needs for its new role as an ambassador, in a way that reduces or eliminates their stress during interactions with trainers, caretakers, and audiences. I remember learning a lot from the writings of Jason Beale of Shaver’s Creek Environmental Center at Penn State, so much that I have included an excerpt below from one of his papers where he describes this cultural shift and the reasons why nature centers may have different, outdated philosophies:

Having worked at nature centers for my entire career, where naturalists suddenly became raptor caretakers, I have a few observations on why there appears to be a very different philosophy toward raptor care, compared to a facility where animal care professionals train the raptors:

Respecting the Raptor’s Wildness – this is the model that I was trained in where the non-releasable raptor is always considered “wild“, despite spending decades in human care, far longer than they were actually in the wild. I had a recent argument with a former staff member who considered this the most “noble” approach. However, what it looked like in application was birds exhibiting frequent escape or avoidance behavior and was dependent on jesses to force the bird into compliance. In short, if a bird could be caught by any method and tied to a glove, it was considered “trained”. There was no attempt to use food or primary reinforcers to train because of the idea that teaching animals “tricks” is something that only happens in zoos (as a facility exhibiting wildlife for education, we are, by definition, a zoo). Chronic broken blood feathers, bleeding ceres, wrists, stumps, and broken flight feathers are “what it looked like”. Despite the poor condition of the birds, they were considered “better off than dead”. I would argue that if that approach were applied to animals in a zoo setting, there would be public outcry.

Naturalists are not animal trainers simply because they can identify or band raptors – Shaver’s Creek, like many raptor programs at nature centers, happened without strategic planning. In 1981, a blind Red-tailed Hawk was available, a mew constructed, and it was used in education. Just as a formerly wild raptor with a disability is unprepared for its role as an avian ambassador without training, so too are naturalists that suddenly become caretakers. At the centers where I have worked, zoos are looked down upon as exploiting exotic wildlife, whereas keeping untrained, non-releasable native wildlife is considered more “honorable”? In other words, to change at Shaver’s Creek, we’ve had to embrace the knowledge and approaches of zoos and our IAATE colleagues. (Beale, 2018)

When this paper was released, I immediately wrote a new raptor program mission statement and 15-page curation plan for the OC and presented it to my managers at the time. They whole-heartedly supported my efforts to follow this culture shift. We also decided to give all the birds names, hoping that would help us see and treat them as individuals.

However, it wasn’t enough for us to just want to change how we handled our raptors. We also needed to know how. That is where the science of behavior change comes in. If you’ve ever heard of B. F. Skinner or Clicker Training, you’ve heard about behavior science. Skinner developed ABA, or Applied Behavior Analysis, which applies the scientific method of observation, hypothesis, and procedure, to change an individual’s behavior, be it human or animal. Basically, it applies the concept that behavior is a tool that organisms use to affect their environment. The frequency of those behaviors is controlled by consequences. Therefore, we can manipulate those consequences to increase or decrease the likelihood of certain behaviors. In other words, we can use rewards or punishments to teach an animal what we do or don’t want them to do. This is done through the observation of an animal’s external behaviors, not by guessing what the animal in thinking or feeling. That’s why it’s science!

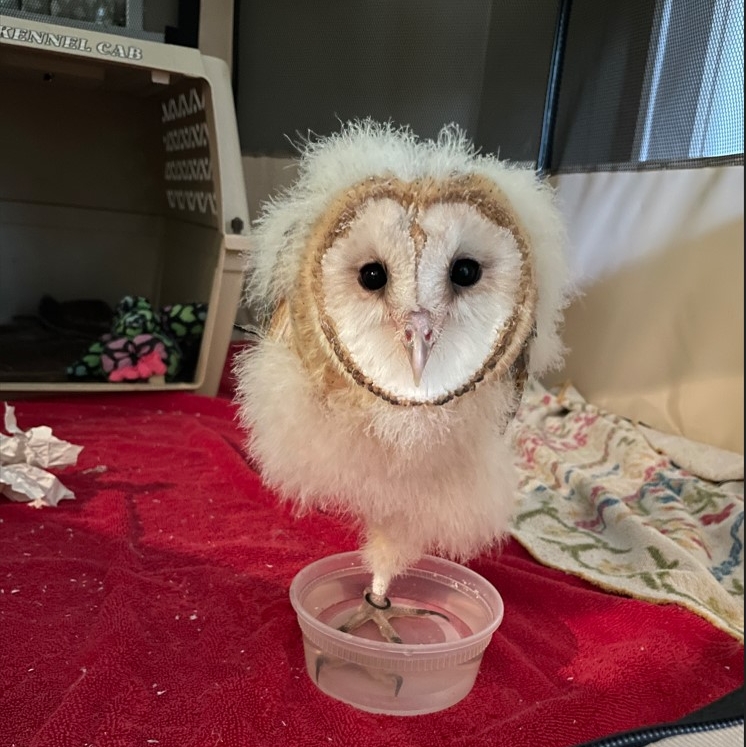

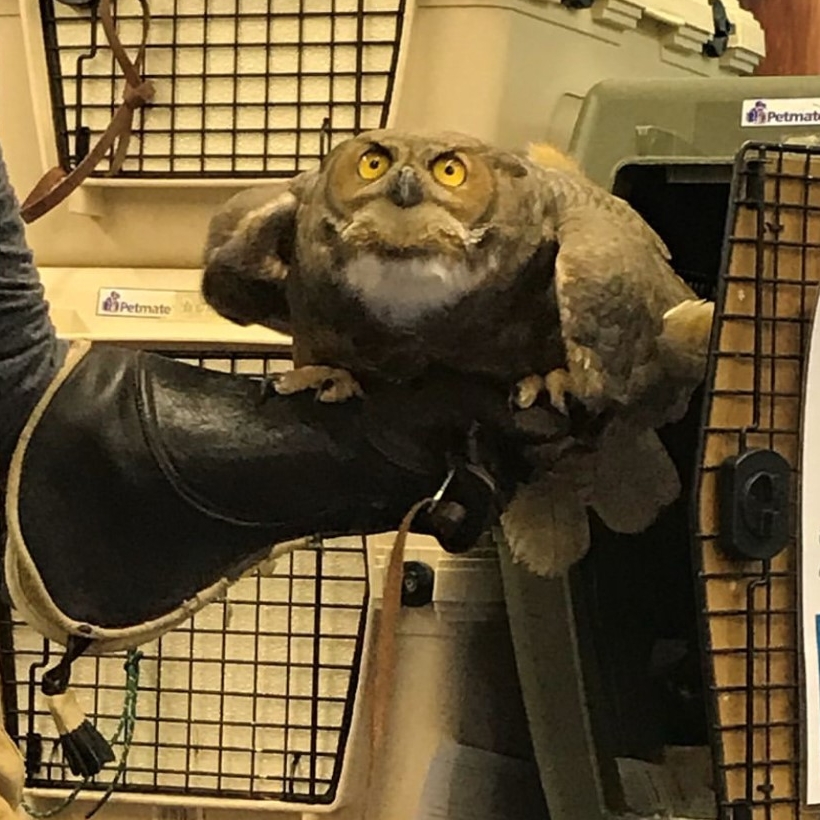

Have you ever heard of operant conditioning? This is when an individual learns about its environment through consequences. Everyone has a learning history, even animals. We all know what we like and what we don’t like, based on our past experiences, and animals are the same. The great thing about ABA is that we don’t have to guess what an animal wants or how it feels. We can look at their behavior and it will tell us. With raptors, some of the behaviors or body language that we look for that might mean the animal “likes” us, is calm body posture, wings tucked in, fluffed out belly feathers, one foot tucked, preening or bathing in front of us, and eating in our presence. Some behaviors that might indicate that a raptor does not “like” our presence is moving away from us, crouching, looking up for a place to fly/escape to, or “ballooning”, which is when the bird sticks its wings and feathers out as far as it can to look big and scary. See the Red-shouldered Hawk photo above.

A Barn Owl, Obi, is in a content/calm posture with one foot in the bath.

A Great Horned Owl is in an escape/fear posture and ready to jump.

Operant conditioning is sometimes called the ABC’s of animal training:

A = Antecedent – cue or environmental stimulus that triggers the behavior

B = Behavior – what the animal does in response to A

C = Consequence – what the animal “gets” as a result of doing the behavior

Clicker training is when a click, whistle, or word, also called a “bridge”, is used to mark the exact moment when the correct or target behavior (B) happens, so that the animal knows exactly what you wanted it to do. For example, when a dolphin trainer does a particular hand motion (A), the dolphin knows to jump out of the water to touch a ball hanging from the ceiling (B). Then trainer will blow the whistle (bridge), indicating to the dolphin that it did the correct behavior and that it can come back to the trainer to get its reward (C).

Although many trainers use mostly food rewards, also called positive reinforcement, as the consequence, there are actually four types of consequences:

+R = Positive Reinforcement – something that is added to the animal’s environment, which results in the increase of the behavior

-R = Negative Reinforcement – something that is removed from the animal’s environment, which results in the increase of the behavior

+P = Positive Punishment – something that is added to the animal’s environment, which results in the decrease of the behavior

-P = Negative Punishment – something that is removed from the animal’s environment, which results in the decrease of the behavior

In this case, positive doesn’t mean good and negative doesn’t mean bad, and punishment doesn’t mean bad either. These scientific terms refer to the animal’s environment, something being added or taken away, and whether that change increases (reinforces) or decreases (punishes) the likelihood of that behavior happening in the future. An example of very humane negative reinforcement that we use with our wild-born raptors is removing ourselves from their environment, which is often something that they want, in order to reward for calm behavior. Oftentimes, these birds are very afraid of us, so much so that they will not eat or accept food rewards in our presence. So, if they are calm or maybe even take a step towards the food while we are watching, we reward that behavior by leaving.

I learned all these different training strategies at two workshops. I attended Contemporary Animal Training at Natural Encounters, Inc. in Florida in 2019, paid for by an Indiana Audubon Society grant, and a Raptor Training Workshop at Avian Behavior International in California in 2020, paid for by the Eagle Creek Park Foundation and ABAS. I got my IATCB Certification in 2021, and I am still learning every day. The raptors that I work with (and my chickens at home) have become so special to me. They all have their own personalities, which I mean very scientifically and also very lovingly. Personality, someone’s likes and dislikes, their favorite foods, their least favorite noise, etc. are all a result of their learning histories, which animals absolutely have. Each of the hawks and falcons that I’ve worked with have been completely different, and their behaviors have changed throughout the years that I’ve worked with them. Hazel, our American Kestrel, for example, used to be terrified of us. She would hide in her box all day, and scream and try to fly away during programs, despite having a disabled wing. Now she trills and acts “excited” to see us, readily hops onto my glove for food, and will eat her favorite food, baby mice, in front of large audiences, even in new places. Though that took literally years of relationship building, gaining her trust, unlearning her previously-learned fear patterns, and teaching her, through operant conditioning, the behaviors that would make her a successful and happy raptor ambassador.

Hazel, the American Kestrel, is happily eating her mouse in the OC reservoir observation room.

It doesn’t stop there. For some of our birds, we have changed the meaning of “successful raptor ambassador”. Only half of our birds are “glove birds”, standing on their trainer’s arm in a classroom or programming space. The other half are “exhibit birds” because, when given the choice, they consistently chose NOT to step onto our gloves, or even actively avoided or attached them. For these birds, Minerva and Matilda, for example, we just redefined what a program looked like with them. For Minerva, the Great Horned Owl, she is trained simply to step out of her enclosure’s dark corner, her comfort zone, for her favorite food, small, whole mice with crunchy skulls, in front of school groups, so that they can see how she swallows her prey. We won’t make her go to the State Fair ever again, unless her personality completely changes.

Matilda the Turkey Vulture is imprinted on humans. This means she theoretically “likes” us, though she would always bite us when given the chance, and would also vomit regularly during programs. We shifted her interactions to mostly “protected contact”. This means that we rarely enter her enclosure with her. We can do so much by targeting her around to different perches and feeding her through the wire. She is trained to hop onto a scale, go into her crate, fly away from us when we point, and lift her foot up onto the wire so we can make sure her feet are healthy. We can’t wait for her new flight aviary to be completed so we can do even more training demonstrations with her.

As you can see, I LOVE talking about these amazing birds, so please visit the Ornithology Center and ask about them. Only Minerva and Matilda are on public display regularly, while the others, except for Luna who is retired, are trained for specific programs, or in training currently. You can find “Meet an Ambassador” posts about each of our birds on our Instagram page. If you’d like to learn more see us at @eaglecreekpark_indy. We have some exciting new plans in the works and ABAS is a part of it, so stay tuned!